When A.C. White died in London in 1902, he was one of the most eminent double bassists of the time. He left an estate valued at £3130 6s 2d, which included a large house in London, eight properties in Canterbury, and a William Forster bass, equating to around £310,000 in 2013 values, at a time when the average salary in Britain was £1.40 per week. Most bassists, in my experience, are also entrepreneurial and business-minded, usually with several different earning streams, with many irons in many fires, and A.C. White was obviously typical of the breed.

Born in Canterbury on 10 October 1830 and baptized on 7 November, Adolphus Charles White was a chorister at Canterbury Cathedral, studied organ and violin with Dr. W.H. Longhurst, and later in Ireland, and is believed to have begun to learn the double bass on his return to Canterbury. He subsequently studied in London with James Howell (1811 – 1879), a leading bassist of his day and whom he often deputized, and went to America in 1853 with the Jullien Orchestra. On his return, he played at Her Majesty’s Theatre (Opera), for the Philharmonic Society, Orchestral Union, and for Jullien’s concerts. When Howell died in 1879, White succeeded him at the Handel Festival, Leeds Festival, Birmingham Festival (1876 – 1888), and Three Choirs’ Festival, much as James Howell had succeeded Dragonetti as Principal Bass at the Opera in London.

A.C. White was a Professor of Double Bass at the Royal Academy of Music from 1880 and the Royal College of Music in London from 1883/4 until he died in 1902. He was awarded an Honorary R.A.M. in 1877 and, according to the RCM website:

In addition [to teaching] he strengthened the College orchestra at rehearsals and at public concerts.

White was Principal Bass of the Royal Italian Opera until 1897 and seven years earlier had been appointed “Musician in Ordinary” to Queen Victoria. During Tudor and Stuart times, the role required musicians to provide music on any occasion for the Royal Household, on call at any time of the day or night. During the 18th and early 19th-centuries, members of the State Band, which performed at coronations, were styled Musician in Ordinary and were entitled to a salary despite often not playing a note for decades! Reforms in 1855 led to the appointment of members of the leading London orchestras, including that of the opera, who were contracted to perform at court each year, including state occasions.

For 22 years, White was organist at St. Philip’s Church, Waterloo Place, London, now demolished, and also found time to compose church music, carols, songs, piano pieces, a Primer for Double Bass alongside at least one solo for double bass and an edition of Dragonetti’s Celebrated Solo. He served in the Volunteer Force described on Wikipedia as:

A citizen army of part-time rifle, artillery and engineer corps, created as a popular movement throughout the British Empire in 1859. Originally highly autonomous, the units of volunteers became increasingly integrated with the British Army after the Childers Reforms in 1881, before forming part of the Territorial Force in 1908.

He retired from the 20th Middlesex Volunteer Force in 1887 with the rank of Major and received a silver sword to acknowledge his services, which he left in his will to his nephew, William Blomfield White.

White married Eliza Anne Barbor in Chelsea on 17 March 1864, and the marriage certificate gives his profession as Professor of Music but no occupation for his wife. His will bequeathed many of Eliza’s paintings to family and friends, and it is likely that she may have been an amateur artist and painted for pleasure. At the time of their marriage, The Gentleman’s Magazine reported that Eliza Annie was the 24-year old widow of Lieutenant Douglas Barbor of the 20th Native Infantry Bengal Army.

In 1887 A.C. White gave a lecture to the Musical Association about the Double Bass, which was reproduced in his Music Primer — The Double Bass, published by Novello, Ewer & Co., probably in the late 1890s, and included details about the various double bass tunings used in different countries. White asserts:

In Italy, as in England, we formerly used three strings tuned in fourths, A,D,G… I was among the first to tune my A string to G, gaining something by that; but as time went on, and we had so much modern German and French music to play — Berlioz, Wagner, Brahms, and others following in their wake — I found it necessary to alter my system in order to fulfil my engagement at the Richter Concerts and add an additional string; and now that I have done so, I like it very much and find it very effective at times.

In 1892 Novello, Ewer & Co. published an Appendix to the Double Bass, written for the four-stringed double bass but with the tuning of G,D,GG,DD — with G as the top string, and included a few scales and exercises alongside many orchestral excerpts. Both works were combined in a new edition in 1934 by F.A. Echlin, this time with the modern tuning we use today, and the editor writes:

The three-stringed Bass, which was extensively used in this country many years ago, is seldom met with now. It may be mentioned, however, that an instrument thus strung is to be recommended for beginners (particularly for young pupils), as the neck and fingerboard are easier for the left hand… The lowest or E string being omitted.

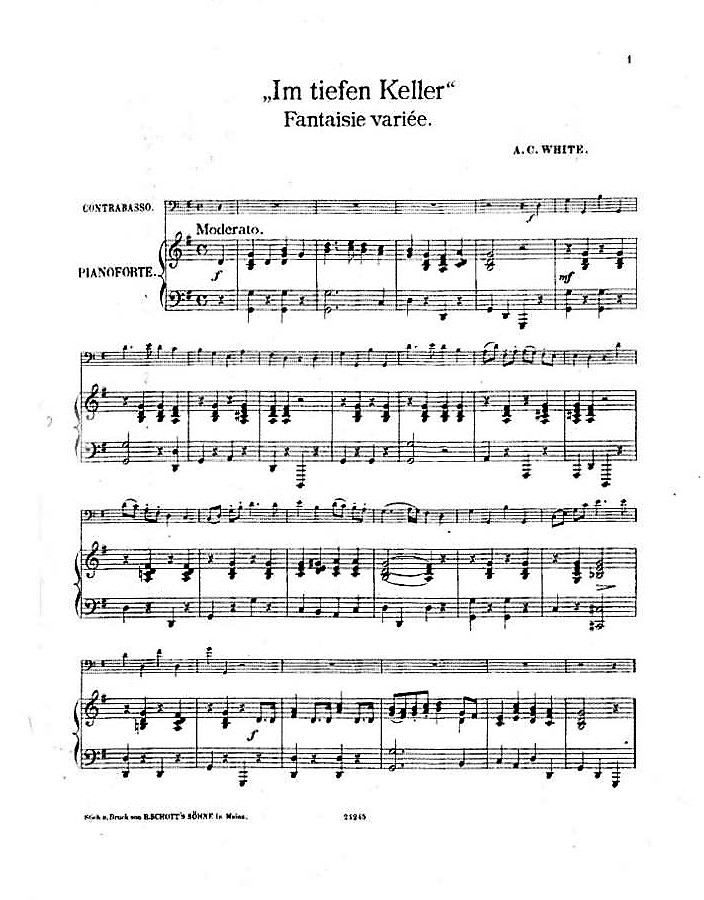

The edition was updated to include orchestral excerpts by Elgar, Holst, and Bliss, which were then relatively new at the time. At the end of the lecture, White played some pieces by B. Tours and Giovanni Bottesini, the Celebrated Solo by Dragonetti, which he had edited for publication, and his own work, Old German Air, “Im tiefen Keller” (with variations). He had mentioned this work earlier in the lecture:

I think it would be a good thing if we could have a conference of double bass players and composers to decide which is the best manner of tuning, as music written for one system does not suit any other, hence the paucity of music written for this instrument. I have myself just published a solo on the German air known as “In tiefen Keller,” but unless the bass is tuned as I use it, it could not be played except with great difficulty and without effect.

It was written for a three-stringed double bass tuned to G,D,GG, and although this tuning works best, it can still be played effectively and with few technical problems on today’s four-stringed double bass tuned in fourths.

Published by B. Schott’s Sohne (Leipzig-London-Paris-Bruxelles), it was titled Im tiefen Keller, “Fantaisie variée sur la célèbre Mélodie allemande pour Contre-Basse avec acc. de Piano,” and was dedicated “à son ami Bottesini.” Recital Music recently published it in a new edition and was probably out of print for most of the 20th-century. The piece is based on a German drinking song called Im kühlen Keller (In Cellar Cool) and a book of folk songs from around the world, with new accompaniments by Sir Granville Bantock, describes it as:

A favorite drinking-song, and it might be said, almost universally known. The words are by Karl Müchler (1802), and the music is attributed to Ludwig Fischer, first bass at the Berlin Opera, who died in 1825. It was evidently composed to suit a voice of exceptional register, the skips being somewhat remarkable even in those days. Many variants exist, but the present version aims at presenting the original as far as possible.

White’s piece is written for orchestral tuning and comprises a theme followed by five variations and a coda. In the key of G major and with a simple and supportive accompaniment, it is typical of the salon music of the late 19th-century, probably composed in the mid-1880s, and demonstrates the entire range of the instrument in music which is both fun and engaging. A four-bar piano introduction introduces part of the theme, which is taken up by the double bass, played in the orchestral register, and slightly elaborated compared to the Bantock version for voice and piano. The chord structure is simple and effective, primarily tonic and dominant, but with a few chromatic harmonies thrown in for good measure.

In teifen Keller would be an ideal piece for the developing bassist who wants to play throughout the entire register of the instrument but possibly isn’t ready for the more advanced Bottesini works yet. Written by a bassist ensures that it is playable, and it would make a fun and lively end to a school or college recital, or possibly as an encore. A.C. White wrote well for the double bass without being too virtuosic or challenging, producing good and honest music which ought to have a place in the repertoire of the progressing young bassist today.

Eliza White died in 1887, aged 51, and her husband remained in their home (36 Parkhill Road, Belsize Park, London) until his death on 4 September 1902, looked after by his housekeeper Helen Davers Liddell. In his will, he bequeathed to her:

All the furniture, bedstead and bedding, pictures, ornaments, carpet, rugs and other articles which at the time Of my death shall be in the back bedroom on the first floor on my said house and also the oil portrait Of myself (with the double bass) now in my said dining room.

He also bequeathed “the sum of Ten pounds to Maggie Flynn now in my service.”

Maggie Flynn was probably a housemaid or cook, and the house in Belsize Park is worth more than £5,000,000 today.

A.C. White and his wife had no children, and many of his friends and family received gifts in his will, which ran to several pages, and does fascinating reading. His death was reported in The Mercury (Hobart, Tasmania) on 29 October 1902 as “Death of the King’s Musician,” with the description “for many years regarded as the leading double bass player in England.”

The Boston Evening Transcript, in America, also reported his death in their edition on 29 September 1902:

Adolphus C. White, Musician — The most famous double-bass player in England, Adolphus Charles White, died suddenly the other day in England, in his seventy-second year, just after a rehearsal for the Worcester (Eng.) festival where he led the bass forces in the orchestra. He won a reputation as a soloist on his ponderous and intractable instrument, and was a musician of versatility, playing the organ and the violin. For twenty-two years he was organist at St. Philip’s Church in London. In 1853 he visited America with Jullien, the French conductor. He wrote a good deal of music, as well as instruction books for the bass, and it is understood — though he never would confess to it — that he originated the popular ditty, “Put Me in My Little Bed,” which had so enormous a vogue at one time. In London he was conspicuous in the performance of chamber music, and his favorite work was Schubert’s “Trout Quintet.”

When researching the life of A.C. White, I was amazed to discover a link to Kate Winslett and Sam Mendes and subsequently to Gwyneth Paltrow and Chris Martin. Both couples had lived at 36 Parkhill Road, owned over a century before by A.C. White and his wife Eliza, Paltrow, and Martin had bought the house from Winslet and Mendes.

Femalefirst.co.uk website noted:

Gwyneth Paltrow and Chris Martin’s new London home is rumoured to be haunted. Previous residents of the plush 3.2millionGBP house, in the city’s smart Belsize Park area, claim the property has an ‘eerie feeling’ and has brought bad fortune to families that have lived there. A neighbour revealed: “The house is quite spectacular but it has an eerie feeling.” It has been rumoured that past inhabitants have been plagued by bad luck and unhappiness. Gwyneth and Chris, who have a baby daughter, Apple, bought the mansion from Hollywood actress Kate Winslet and her director husband, Sam Mendes last month. It is not known whether the couple, who have two children, Mia and Joe, experienced any supernatural vibes, but the neighbour added: “Sam and Kate didn’t live there for long, so maybe they weren’t happy with the place.” However, sources believe Chris and Gwyneth’s extensive renovations of the house may eradicate any bad luck. One said: “Hopefully, now the new owners have gutted it, the bad vibes might have been chased out.”

A post on The Paranormal and Ghost Society website, by Mike Baron on 15 January 2006, denies the claims:

But a spokesman for Paltrow says there’s not a ghost of truth to the tale. “This is 100 percent false,” he told The Scoop. “[Paltrow] does not feel her home has any bad energy, and, in fact, feels that the house has wonderful energy and enjoys all the time she and her family spend there.”

There was talk of an exorcism, which was probably invented by the fevered imagination of a tabloid journalist who had several column inches to fill. Was A.C. White haunting his old house? Maybe he wasn’t a fan of Titanic or Coldplay… And was there any truth in the story in the first place? Who knows, but it does make an intriguing end to an article about a 19th-century bassist who was respected and much admired during his lifetime but has been largely forgotten as time has moved on. Hopefully, this short Bass Blog will please A.C. White and introduce his name to new generations of bassists.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the life and legacy of A.C. White, the eminent 19th-century double bassist, provide a fascinating glimpse into the world of a musician whose influence extended far beyond his musical achievements. From his prestigious positions as Principal Bass of the Royal Italian Opera and Professor of Double Bass at esteemed institutions like the Royal Academy of Music and the Royal College of Music, to his service in the Volunteer Force and organist role at St. Philip’s Church, White’s multifaceted career reflected the dynamism of a musician deeply embedded in the cultural fabric of his time.

White’s contributions to double bass pedagogy, evident in his lectures and writings, showcase not only his technical expertise but also his adaptability to the evolving musical landscape. His reflections on tuning and the evolution of the double bass highlight a keen awareness of the instrument’s changing role in orchestral settings, as seen in his innovative approach to accommodate the demands of contemporary compositions.

Beyond his professional life, A.C. White’s personal story, intertwined with that of his wife Eliza, adds a layer of humanity to the narrative. His bequests in the will, including detailed provisions for his housekeeper and acknowledgment of his late wife’s artistic pursuits, reveal a man with a sense of generosity and appreciation for the arts.

The unexpected connection between A.C. White’s former residence and subsequent inhabitants, including notable figures like Kate Winslet, Sam Mendes, Gwyneth Paltrow, and Chris Martin, adds a curious twist to the tale. The rumors of the house being haunted inject an element of intrigue, prompting speculation about the ghostly presence of A.C. White himself. While such claims may be dismissed as sensationalism, they contribute to the mystique surrounding the legacy of a musician whose impact resonates across time and even enters the realm of popular culture.

In the end, A.C. White’s story is a reminder that the echoes of a musician’s life can extend far beyond the notes played on the double bass. As we explore the rich tapestry of his experiences, from the concert halls of 19th-century England to the rumored hauntings in a London mansion, we are invited to appreciate the complexity of a life dedicated to music and its enduring, if sometimes spectral, influence on the world.