The historical data of trumpets in Spain is very scarce, thus a discography of Spanish baroque music in which the trumpet participates as a solo instrument is practically nonexistent. It is necessary to cover this gap and put value into the enormous historical musical heritage of Spain. To do this, there is a need for musicological research that supports the interpretation of this music.

During my studies at the Music Conservatory of Bologna (Italy) with maestro Igino Conforzi and motivated by this deficiency in Spanish baroque music for trumpet, I decided to focus my thesis on the investigation of the trumpet in the Spanish court. The result of this research is this very interesting album.

The recording used the organs of Torre de Juan Abad, Ciudad Real — a magnificent instrument representative of the Spanish system of the XVIII century — and Gilena, Seville — also of the eighteenth century, with a characteristically deep and warm sound. Igino Conforzi, my teacher, also participates as a musician in this recording.

Research Work

The music selected for this recording is from the Spanish Baroque repertoire compiled by the Franciscan priest, organist, composer and collector of music Antonio Martín y Coll (1660-1734) in various books published at the beginning of the eighteenth century, specifically between 1706 and 1709.

Although this music was originally composed to be played by organists, a substantial part was in fact influenced, in compositional terms, by the prevailing performance style of the time that employed clarines, the name given to the trumpets played in the upper register, also known as the clarino register. Early evidence points to their use on solemn occasions thanks to the brilliance of their sound.

“A small, high-pitched trumpet called clarín because of the clarity of its voice.”

Cobarruvias, 1611, p. 147

It was hardly an accident that the clarino style should be taken up for adaptation to organ composition. It surely arose from the importance acquired at the end of the seventeenth century by the horizontal pipes of the Spanish Baroque organ on the main façade, named batalla (“battle”). This piping, together with the internal reedwork, led to the configuration of registers such as: clarines, trompeta magna, trompeta real, clarín de batalla, clarín de campaña, clarín de eco, clarín de bajos… These registers may have been installed in organs just because of musical taste, or to substitute for trumpets, the inclusion of the clarín, an instrument for military use, in musical functions in the church perhaps not considered appropriate. Otherwise, a lack of financial liquidity did not allow the cost of contracting a trumpet corps to be met.

As the influence of true clarines on the composition of music for organ is quite clear, particularly in battles and and pieces for clarines, it has been the aim in this recording project to create an extremely interesting parallel between the organ and the original instrument, “the natural trumpet”, it sought to imitate. This implies a return journey to the instrument of origin which one day embarked on the outward journey to contribute with its performance style to the splendour of the Iberian organ’s pipework. Use of percussion was a perfect complement to the clarines, emulating past times when trumpets and kettledrums (timbales) took part in military or civilian activities, always at the service of the court or the authorities, as yet far from being included in cultivated music. For that, it was necessary to wait until the second quarter of the seventeenth century in Central Europe (in Spain, this was to happen later, the first bibliographical reference to the appearance of trumpets in non-martial or civilian activities being dated 1701, with the incorporation of two clarines onto the staff of the Royal Chapel at the Royal Palace in Madrid).

Antonio Martín y Coll and the Music for Clarines

Not a great deal of information is available about the life of Antonio Martín y Coll. He is known to have come into the world in the Catalan locality of Reus, possibly about 1680. Apparently very young, he took the orders of St. Francis and moved to Castile, taking up residence at St. Didacus convent in Alcalá de Henares where he received lessons from the organist Andrés Lorente (*1634 †1703), known today because of his major Treatise on the Why of Music (1672). Martín succeeded Lorente as senior organist at the convent, moving to the court in 1707 where he held the post of senior organist at St. Francis the Great until his death in 1734.

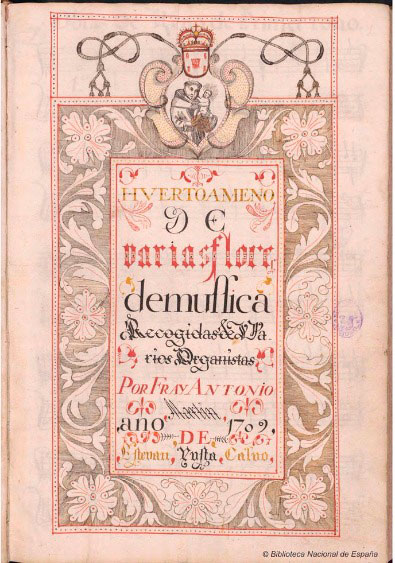

Fray Antonio Martín y Coll diversified his work, as had his maestro Andrés Lorente, into the three facets of composer, performer, and writer of treatises. Modern interest in him is however usually more as organist composer and in particular as the compiler of a huge collection of keyboard music from various sources and for varied uses, known to us thanks to ve handwritten notebooks dated between 1706 and 1709, held in the National Library in Madrid.

Martín y Coll’s notebooks usually conceal their authorship, but research has identified many composers there, from Cabezón, Aguilera de Heredia or Cabanilles to Louis Couperin, Frescobaldi, Lully or Corelli. It is moreover extremely interesting to confirm that there is not just plenty composed for the keyboard but also transcriptions and adaptations of other instruments and for instrumental ensembles. Thus Martín y Coll is witness to and participant in a well-established tradition of using certain instruments to emulate the repertoire of others, as far as possible imitating their sonorous characteristics.

This was the case for example with a collection of 29 Diverse songs for two clarines, plus another piece For solo clarín with accompaniment, copied in the volume entitled Huerto ameno de varias flores de música (A pleasant garden of various music flowers), dated 1708 (E-Mn, M 1359). These scores, usually treated as keyboard music as part of the tradition of the battles and works for reed, reveal their direct origin in the sounding of clarines, to the point where it can be said that they in fact are for clarines (natural trumpets) and not for organ with clarino registers, although they might be played and imitated on the organ. Most of these pieces, both the two clarín songs (unaccompanied) and the solo works (accompanied) use exclusively the notes available within the clarines natural harmonic series, creating a type of music quite different from the compositions for split-keyboard organ with clarino register which, while imitating war calls, extends to all the split registers, going beyond the possibilities of a true clarín.

Thus Martín y Coll offers the opportunity to learn of genuine clarín calls and pieces likely to be in use at the end of the seventeenth century and the start of the eighteenth. It must not be forgotten that clarines, generally associated with the kettledrum or timbales, fulfilled a musical role but also, and above all, constituted a sonorous signal of a heraldic and even martial nature with precise and recognisable aims, evoking calls to diverse military actions as well as the sounds proper to different lords, houses, families, institutions, etc. All recall the famed Toccata preceding the music for Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (and which he reused as a quote a little later at the start of his Vespers), a piece, a sort of sonorous pennant or shield belonging to the Gonzaga Mantovanos, that its subjects, citizens, and residents probably identified with its very first notes. The same may have occurred with at least some of the few similar examples known to us from the seventeenth century Hispanic repertoire, such as the well-known tocata de chirimías (in fact typical clarín music) used by Joseph Ruiz Samaniego in an Epiphany carol in 1664 and cited by Pablo Bruna too in one of his contrapuntal tientos. Martín y Coll’s collection enlarges this panorama significantly, at the same time making it possible to speculate and reflect, with ready arguments, about the significance for the musicians and listeners of the time of the use of these compositions outside their original context, making this happy initiative to recover this music with the instruments for which it was presumably written a cause for celebration.

Conclusion

“Clarines de Batalla” emerges not only as a musical exploration of the Spanish Baroque repertoire but also as a historical journey to resurrect and celebrate the significance of clarines in their original context. This album is a testament to the vibrant musical traditions of Spain, shedding light on the intersection of musical and historical narratives that define our cultural heritage. Through meticulous research and a dedication to authenticity, this project aims to bridge the gap in our understanding of Spanish baroque music, providing a platform for the clarines to once again resonate with their historical significance. In reviving these compositions, we not only pay homage to the musical legacy of Antonio Martín y Coll but also offer a unique glimpse into the sonorous signals of a bygone era, where clarines played a pivotal role in heraldic and martial contexts. “Clarines de Batalla” invites listeners to immerse themselves in the rich tapestry of Spain’s musical history, experiencing the evocative sounds that once echoed through the courts, churches, and military events of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.